Methodological (soft) reductionism

A research strategy to analyse systems by breaking them down into their constituent parts, and studying those parts in isolation.

Allows that new variables/laws are needed for different levels, that explanations may also run downward via constraints, and that multiple realizability is possible.

Hard (ontological) reductionism

Higher-level things / regularities are nothing over and above lower-level ones (i.e. can in principle be fully explained in terms of them).

Totally fine with non-clockwork physics (quantum fields, chaos, non-linear dynamics, …).

Allows weak emergence; no new fundamental forces/laws are needed at higher levels.

Mechanistic reductionim / mechanistic materialism

“Systems are best understood as machines: Decomposable parts, local pushes and pulls, linear bottom-up causation, linear bottom-up causes only. Wholes = sum of parts. No qualitative leaps. Higher level vocabularies (biology/psychology/…) are just convenience.”

When really taking opposing reductionism serious, we need to ask ourselves: How do the multiple scales interact with eachother, …?

Link to original“Trying to play chess with Laplace’s Demon”

It’s possible to perfectly predict the next state of a CA just by following the local base rules, but you’ll never build a glider or turing machine etc., without considering mesoscale properties. All the microstates are equal to him, winning, loosing, pieces, are nothing to him.

The molecular story is not the whole story.

We might for example not be able to describe the activity of a place cell, just by (even if as accurately as possible) measuring all the biochemical gradients and properties in its environment, be able to make sense or predict its firing patterns. The semantic content / aboutness of the place cell responding to a particular spatial location is escaping our ability to describe it in the terms of biochemestry.

The efficacy of the theory / perspective would have a noise term left over, corresponding to the efficacy of something else - the fact that it is about something, not just pure biochemestry.The efficacy of a prediction with the biochemical lense decreases, as the interactions get more complex . significantly - there are more things to keep track of that are not just biochemical - the noise term gets bigger.

For example, when the co-regulation between two people increases, their inter-brain synchrony goes down. When you are regulating your actions not just based on your own interests, but also taking into account what another person is doing and what their interest might be, it increases the complexity of the things you need to care about

The same is true for things happening within an organism: The more things a cell has to care about, the more noisy it will be. Where noisy doesn’t mean actual noise, it looks like noise to you, when taking the quantitative lense of the biochemist, measuring in terms of voltage / chemical concentration / … you are not measuring what is written in the system’s genes / what is happening in some other system / at the whole-cell level.

→ A limited perspective will always have a remainder of efficacy that is coming from somewhere else, not intelligible from a narrow point of view.

→ The noise term overwhelms the rest over time. The influence fo the “other stuff” grows, the more your are an agent oriented towards the future (higher-level interactions with other agents, what you or they are doing, …).

Like analysing a chess game on a molecular level: It won’t get you to the next thing / you won’t learn from it.

It is a fine story for an immediate analysis, but not useful for later on. “You live your life forwards”.

Link to originalDiscretization & Separating the parts from the whole (also called methodological reductionism - quite successful in neuroscience (and ML) thus far, but approaching its limits - though advances in technology keep its “death” at bay).

Without a clear goal or definition of intelligence, the field of AI got split into discrete sub-fields (CV, NLP, …), with a 0.5% test set improvement as the goal, not bringing the fields together whatsoever.

Similarily with neuroscience, where there are vast amounts of observational data, but parts of the brain are studied in full isolation etc. and there have been little attempts to try to put it all together and craft theories for the observations (Jeff Hawkins explained this at his first lex appearnce).

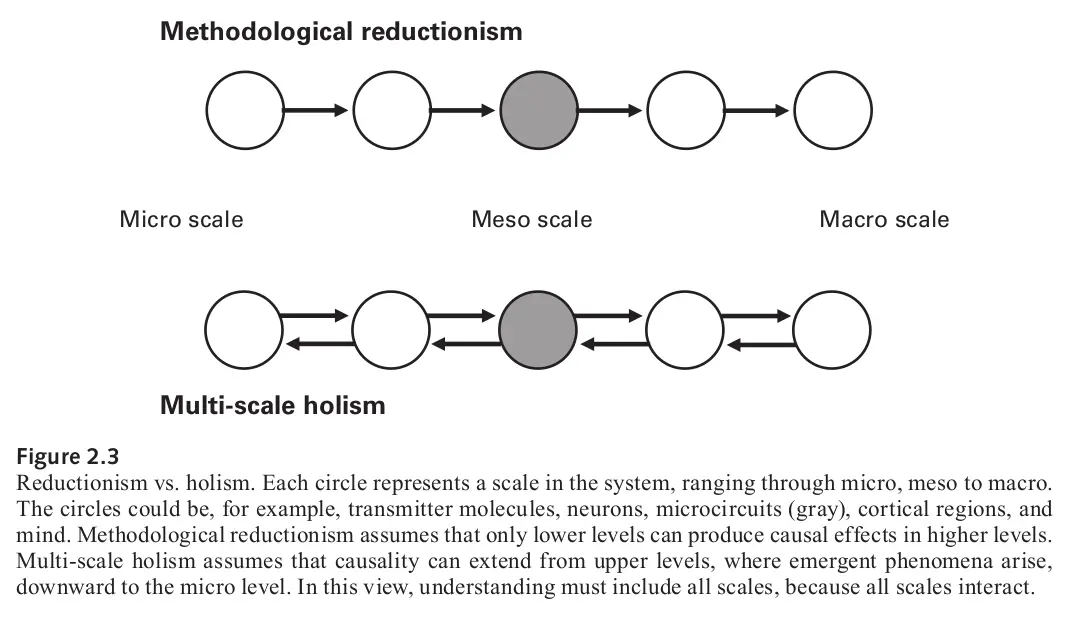

Link to originalComprehending emergent phenomena can be difficult because we have been trained to analyze most systems, including complex ones, by taking them apart (methodological reductionism).

The problem is that most emergent phenomena disappear when they are taken apart. How then can we understand them? We must learn to shift our focus away from the parts themselves and onto the interactions between the parts. Sometimes these interactions do not even depend on the types of parts that are present. In describing emergent phenomena, we will have to address some issues that are essentially philosophical in nature.

Emergence is not something magical that jumps into being. Programs that we run on computers are clearly emergent too (just transistors, just atoms and molecules, …, high level languages), we just don’t tend to think about it like that, since we are able to wrap our minds around it.

Technology often drives methodological reductionism.

If we have the means to affect a single ion, a single neuron or a single gene, then we can explore with relative ease the consequences of manipulating those things. If most of our experiments involve causal manipulations at the lowest levels, we could gradually develop the view that the arrow of causality only runs from the bottom up.

But higher levels can cause things to happen at lower levels… see also: emergence.

Circular transclusion detected: general/emergence

References

Conversation between Josh Bongard, Atoosa Parsa, Richard Watson, and Michael Levin