Notation:

TLDR:

- A square matrix is invertible its determinant is non-zero its rank is full (equals its size ).

- It is the product of its eigenvalues (If is a diagonal matrix, its determinant is ).

- This tells us how volume in -dimensional space changes when transformed by the matrix.

- Defined only for square matrices because only they map -dimensional space to itself.

Determinant

Properties 4-10 are derived from the first three, which form the basis of the determinant definition.

1]

2] Exchanging two rows changes the sign of the determinant

→The determinant of a permutation matrix is if the number of row exchanges is even, else .3a] … multiplying a row by a scalar is the same as multiplying the entire determinant by that scalar.

→ The determinant behaves like volume: .

3b] … determinants are column.

Note:4] Two equal rows →

By property 2, if the sign changes but the matrix is the same, the determinant must be zero.

Confirmed by the fact that the rank of the matrix is less than its size .5] Subtracting a multiple of one row from another does not change the determinant.

6] Row of zeros →

7]

… the determinant of a triangular matrix is the product of its pivots.

We can simply eliminate the stars by multiplying the rows with the corresponding . This leaves us with a diagonal matrix. By rule 3a) we can pull out the from the determinant, leaving us with the product of the pivots times (property 1). You need to keep track of row exchanges made (property 2).

→ So the algorithm for finding the determinant, when is invertible is .

For a matrix:

→ If is , we can exchange rows (property 2) first, if is also , then the determinant is (property 6).

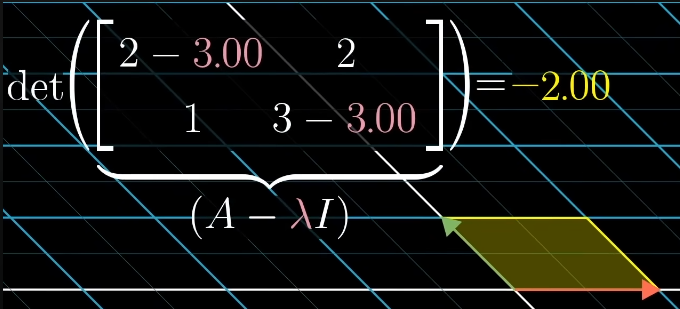

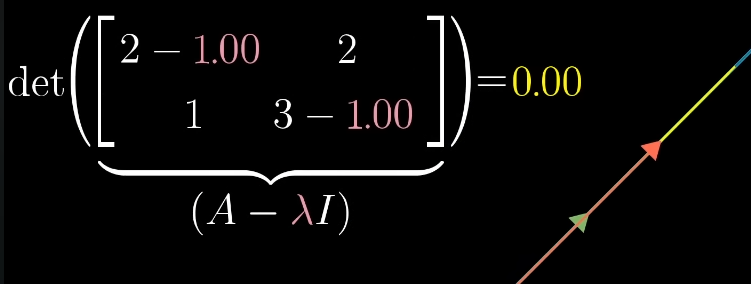

8] iff is singular (not invertible).

The determinant is zero if one of the is zero, which means we can construct a row of zeros → not linearly independent.

9]

For diagonal matrices it’s easy to see why:

.This tells us how we can calculate :

Which, again, is easy to see for diagonal matrices: , .What’s more, it shows us that:

, and

… from 3a … behaves like volume!10]

There is nothing special about “row1”, because we can exchange rows (property 2) and there is nothing special about rows in general, because we can exchange rows for columns.

The proof for 10) is also about bringing the matrices into triangular forms (1s on the diagonal).

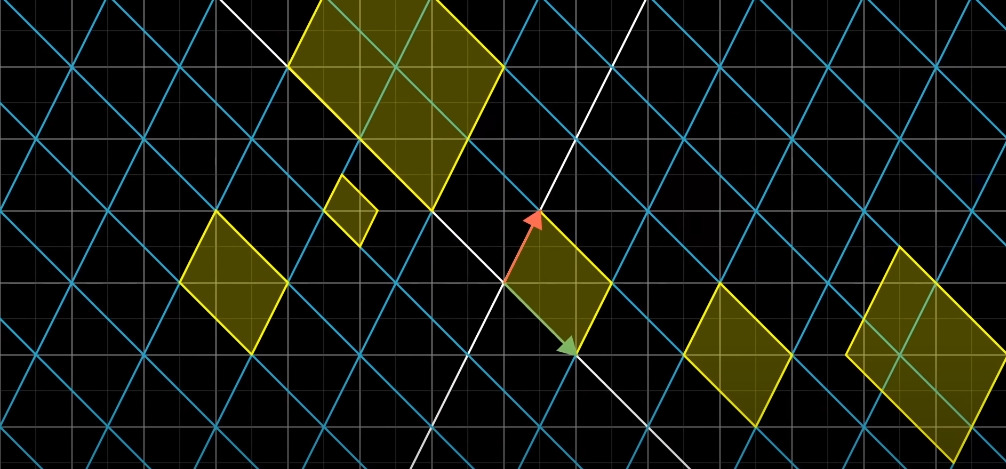

Visual Intuition.

The absolute value of the determinant is the Area/Volume/… in /… etc after the transformation described by the matrix has taken place on the unit square/cube/… etc.

It is easiest to grasp the changes of a matrix multiplied with another matrix / set of vectors does, by visualizing how it transforms the unit vectors of of the vector space:

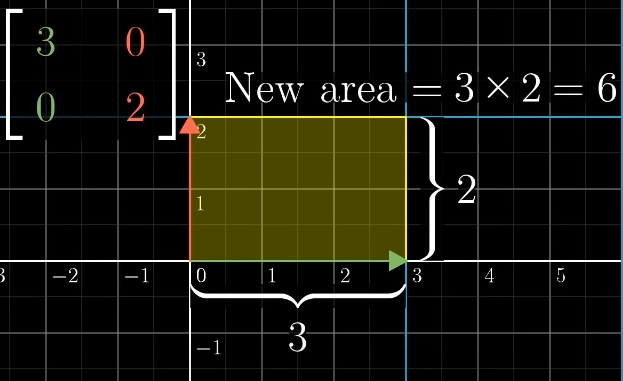

The matrix multiplies by 2 and by 3, scaling the area of the unit square by :

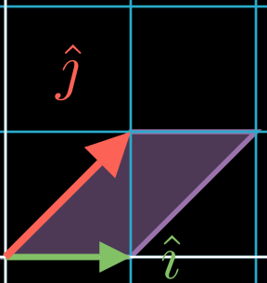

A shear matrix like tilts the coordinate system and the unit square into a paralellogram.

For this particular , the Area of the resulting parallelogram will stay the same

():

The determinant tells us how every area on the entire space changes in size.

The elements of the transformation matrix tell us about the shape. As we are dealing with linear transformations, the grid lines always remain parallel and evenly spaced.

If , then the transformation changes the space in a way that it collapses to a lower dimension (for the case of it may be a plane, line or point: anything with 0 volume).

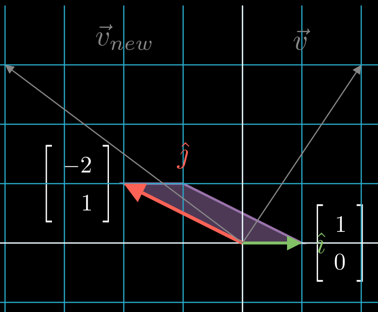

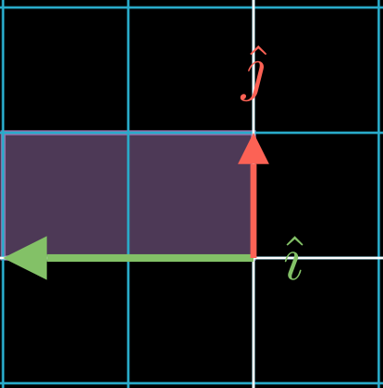

Negative elements mean that the positions of and have been switched.

for example puts to the left and multiplies it by two. The resulting determinant/area will be :

Computation.

Elimination gaussian elimination to obtain a triangular matrix. The product of its diagonal entries is the determinant.

We can use

If you interchange (swap positions) of two rows, you need to multiply the resulting determinant by .

So for an even number of swaps, the sign stays the same.

For matrices:

Intuition:

scales , scales . Multiplying them gives the area of the bigger / smaller rectangle.

If or is , we have a parallelogram, still with area . (If only or changes in general, the paralellogram gets more / less stretched out, but area stays .

Squished rectangle / parallelogram:

→ Area stays the same.

→ The unit vectors of the original vector space form the identity matrix.

→ The new unit vectors equal the columns of the transformation matrix:

If any of the diagonal entries are , the matrix is not invertible/squashes the space to a lower dimension. If it is different from , the matrix has full rank.

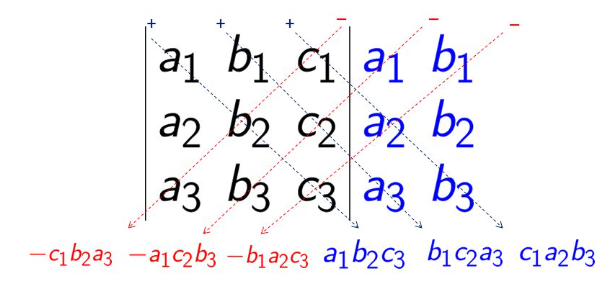

Rule of Sarrus for calculating determinantes for matrices up to :

See cofactor expansion for a recursive method to compute determinants of larger matrices.

Determinant x linear systems of equations | Cramer’s Rule

A system of linear equations can be represented as a matrix equation .

If is invertible, we can solve for :

If is not invertible, there is either no solution or infinitely many solutions.

The determinant tells us whether is invertible (non-zero determinant) or not (zero determinant).

More concretely, consider the system of equations:

\begin{align} \text{I:}\quad & a_{11}x_{2} + a_{12}x_{2} = b_{1} \\ \text{II:}\quad & a_{21}x_{1} + a_{22}x_{2} = b_{2} \end{align} $$ We can solve for $x_{1}$ by multiplying I by $a_{22}$ and II by $-a_{12}$ and adding them: $$ \begin{align*} a_{22}(a_{11}x_{1} + a_{12}x_{2}) & = a_{22}b_{1} \\ -a_{12}(a_{21}x_{1} + a_{22}x_{2}) & = -a_{12}b_{2} \\ \hline (a_{11}a_{22} - a_{12}a_{21})x_{1} & = a_{22}b_{1} - a_{12}b_{2} \\ x_{1} & = \frac{a_{22}b_{1} - a_{12}b_{2}}{a_{11}a_{22} - a_{12}a_{21}} \end{align*} $$ Similarily, for $x_{2}$, we get: $$ x_{2} = \frac{a_{11}b_{2} - a_{21}b_{1}}{a_{11}a_{22} - a_{12}a_{21}} $$ Their common denominator for $x_{1}$ and $x_{2}$, $a_{11}a_{22} - a_{12}a_{21}$, is the determinant of the coefficient matrix! → If the determinant is zero, the equations are either parallel (no solution) or identical (infinitely many solutions). → There is redundancy in the equations, they do not span the entire 2D space. Furthermore, the numerators can be interpreted as determinants as well, so we can write the solutions as:\begin{align*}

x_{1} &= \frac{\begin{vmatrix} b_{1} & a_{12} \ b_{2} & a_{22} \end{vmatrix}}{\begin{vmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} \ a_{21} & a_{22} \end{vmatrix}} = \frac{1}{\det A} \begin{vmatrix} b_{1} & a_{12} \ b_{2} & a_{22} \end{vmatrix}, \quad \ \

x_{2} &= \frac{\begin{vmatrix} a_{11} & b_{1} \ a_{21} & b_{2} \end{vmatrix}}{\begin{vmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} \ a_{21} & a_{22} \end{vmatrix}} = \frac{1}{\det A} \begin{vmatrix} a_{11} & b_{1} \ a_{21} & b_{2} \end{vmatrix}

\end{align*}

A^{-1} = \frac{1}{\det(A)} \begin{bmatrix} d && -b \ -c && a \end{bmatrix} = \frac{1}{ad-bc} \begin{bmatrix} d && -b \ -c && a \end{bmatrix}

## References [3b1b: The determinant | Chapter 6, Essence of linear algebra](https://youtu.be/Ip3X9LOh2dk) [18. Properties of Determinant (Gilbert)](https://youtu.be/srxexLishgY)