Convergence

We say that the sequence converges to iff:

where is the epsilon neighbourhood of .

We then call the limit of the sequence and write:The sequence is called convergent, or we say that its limit exists, if such an exists. Otherwise, the sequence is called divergent.

The limit does not depend on the finite number of initial terms.

If is a sequence with for almost all , i.e. there exists such that for all , then .

Convergence means oscillations must die out

The definition demands: for any (no matter how small), eventually the sequence stays within that -ball forever. This is stricter than boundedness. A sequence can be bounded yet divergent if it keeps jumping around.

Complex convergence

For with :

For any , the archimedean property gives with .

Then for : .

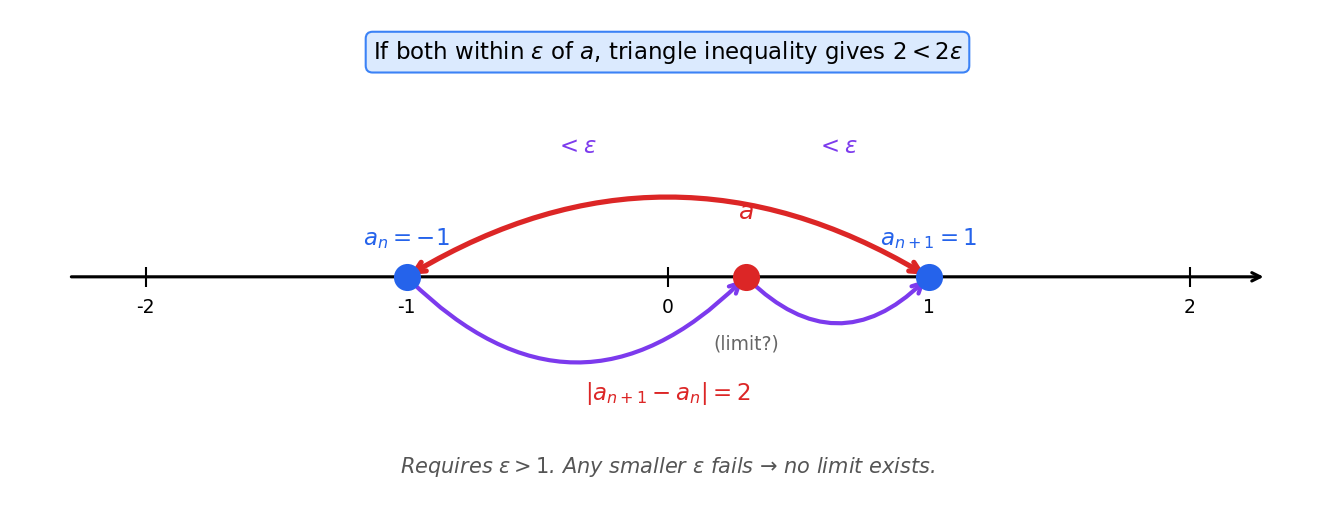

is divergent

Proof by contradiction: suppose for some .

Pick . By convergence, there exists with for all .

But consecutive terms satisfy , so they can’t both lie in a ball of radius . Contradiction.

Any works. If both , the triangle inequality gives:

But , so we need , i.e. .

Definite divergence (improper limits)

Let . The sequence tends to (or ) if

We write or , and call the improper limit.

Tendency to is defined analogously with .If a sequence tends to , it is called definitely divergent.

Definitely divergent sequences are necessarily unbounded (no finite bound can contain all terms). They can still be bounded from one side: diverges to but is bounded below.

This concept only applies to real-valued sequences. Complex numbers have no compatible order, so “tending to infinity” in isn’t defined this way.

Link to originalLimit arithmetic

Link to originalSandwich rule